The recently released 50 Design Ideas You Really Need to Know book features essays tracking the evolution of design from the 19th century until now. Here, its author chooses five key design ideas.

The latest in a series of 50 ideas books, the 50 Design Ideas You Really Need to Know aims to cover a wide range of design concepts and make them accessible to the interested layman reader.

“Its 50 ideas could perhaps be better described as a mixture of movements, mediums, concepts, processes, management techniques and marketing ploys, all introduced in a, hopefully, insightful and enjoyable manner,” its writer, John Jervis, told Dezeen.

“My rationale for taking this on would, possibly, be along the lines that it was an opportunity to introduce some key design topics to the reader (and myself) in an accessible fashion, while also adding a bit of shade to indicate that there’s often more to design than immediately meets the eye, or confronts the Wikipedia reader.”

Here, Jervis selects five out of those 50 ideas, which he said “made me pause for a moment while writing, and change my intended script a little”.

Design Museums

“Including design museums in the book was a little contrived, but these institutions have reflected – and influenced – contemporary ideas about design to an enormous degree.

“The founding of London’s Victoria & Albert Museum in 1851, skimming off some of the Great Exhibition’s profits to purchase ‘correct design’, led to an astonishing number of replicas around the world – Vienna, Buenos Aires, Prague, Sydney, Chicago, Oslo, and on and on.

“Most shared the goal of improving public taste and manufacturing outputs – Leipzig’s Museum für Kunstandwerk, for instance, announced its goal ‘to take action against the archaic ways and pathetic mediocrity of German industry’.

Exploring the twists and turns over the ensuing years – the impact of industrial design and modernism, the influence of New York’s Museum of Modern Art, the fluctuating status of the curator and the exhibit, the arrival of ‘high design’ and (more recently) the ‘design is everything’ mindset – explains so much about how design reached its current lofty position, and definitely deserves a book of its own.

Designing for play

“The role of an introductory text is, by and large, to be dispassionate, so this one largely retells the tale of modernist toys – colourful Bauhausian blocks and abstracted animals intended to nourish imagination and creativity with open-ended play, rather than mimick the adult world, or lock into existing stories.

“Yet the market for these perfectly crafted wooden objects has long been parents or godparents. Toys children actually play with, such as the phenomenally successful Star Wars toys mass-produced in Hong Kong from the 1970s, tend to come equipped with fully formed universes and enthralling narratives.

“The trajectory taken by the most famous modernist toy of all – Lego – proves the point. The company’s singular focus on its colourful universal blocks, introduced in the 1950s, lasted only a couple of decades. As savvy rivals flourished, it introduced ‘themes’ to compete – Space, Castle, Pirates and so on – each with specialised blocks and definitive instructions.

“Star Wars and Harry Potter followed, and eventually Lego’s own movie universe. The modernist dream of play had been replaced by boxes of joyful plastic, yet today we still venerate a bunch of dusty wooden ornaments. Sometimes design is confusing.”

Craftivism

“One of the most likeable ‘ideas’ in the book, with a history going back to the Suffragettes and beyond, Craftivism – a term coined by Betsy Greer in 2003 – has been called ‘protest for the introverted’. Utilising often denigrated skills such as embroidery and knitting, those who struggle with the intensity of civil disobedience and protest marches can contribute to social movements, making their voices heard.

“The most famous example, 2017’s Pussyhat Project, resulted in the emotional sight of a sea of pink in the US capital, as tens of thousands of marchers wore hats based on a downloadable pattern – some knitted by themselves, some by supporters across the country.

“Donald Trump’s political durability, despite this powerful protest against his inauguration and his language, suggests that in today’s fractured landscape turning craft into craftivism may not have the desired results. As with celebrity endorsements, the liberal elite tag can be highly destructive of even the best intentions.

Art deco

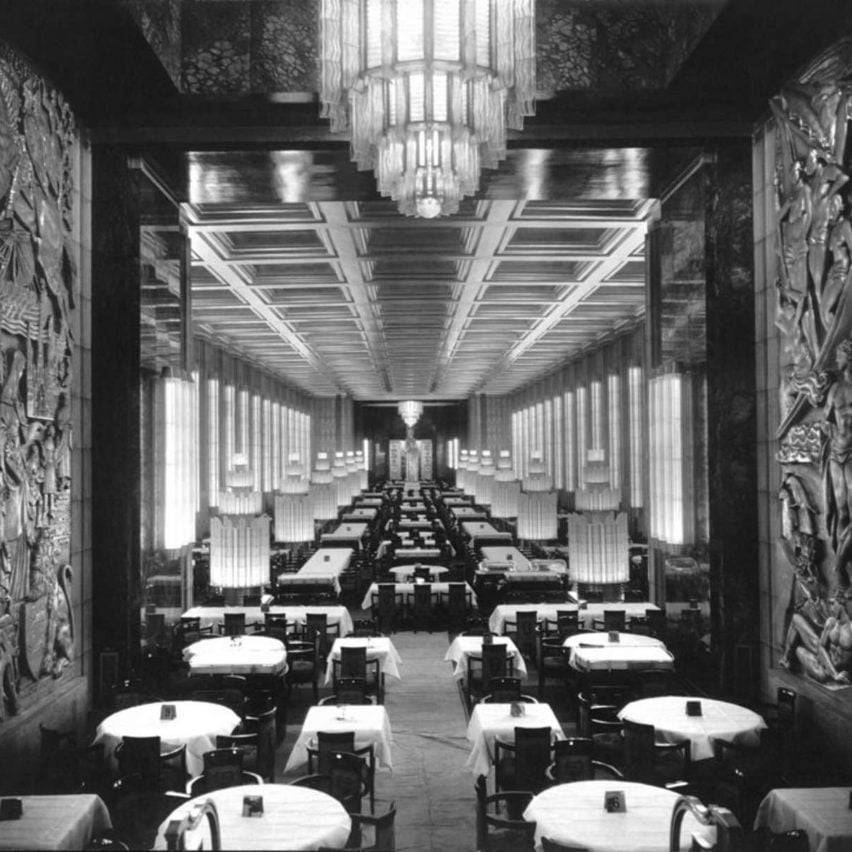

“Most of the book’s entries come with a side panel – on an exemplary object, exhibition, individual, group, or even idea. For art deco, it’s the ocean liner. I hadn’t really considered them before. They don’t seem real, existing only as extravagant settings for period films, or gorgeously sleek silhouettes on airbrushed posters. But they were real, and extraordinary.

Subsidised by the French government, the SS Normandie drew on leading artists, architects and designers for its hugely opulent art deco interiors. The glass-clad dining room by Pierre Patout, for instance, stretched even longer than its famous model at Versailles.

“Today, it seems inevitable that modernism would go on to define our world. In 1932, when the SS Normandie launched, and an ailing Bauhaus struggled to get a few chairs manufactured, this colossus expressed internationalism, travel, style, industry and modernity. It expressed the machine and the future. Perhaps, if things had taken (quite a few) different turns, we would be living in an art deco world.”

The Bauhaus

“When writing this book, I hugely enjoyed revisiting design movements old and new, coming out of the experience with renewed admiration for their protagonists and works.

“But, most of all, it confronted me with the extraordinary achievement of the Bauhaus during its fifteen-year existence from 1919 to 1933 – just 15 years! And that’s to say nothing of its influence in education and industry as its teachers, students and disciples spread across the globe.

“The impact and importance of the Bauhaus is taken for granted, so much so that it has become almost invisible. It was salutary to be reminded of the unparalleled mixture of practical and intellectual experimentation, commitment, radicalism, productivity, rigour, freedom and joy that emerged from its workshops – elements evident in other movements, but never all together, and not captured in my text, much as I tried. So most of my advance was blown on a small black side table with tubular-steel legs.”