In the 1970s, the humanist geographer Yi Fu Tuan speculated that “in some ideal future, our loyalty will be given only to the home region of intimate memories and, at the other end of the scale, to the whole earth.” Half a century later, Energies at the Swiss Institute adopts Tuan’s dual vision while dispelling any notion of an ideal attained. Instead, the show’s hyperlocal roots and global reach offer a trenchant critique of the power relations that inhere in the act of generating energy. The spark is a story of grassroots activism set in the 1970s East Village.

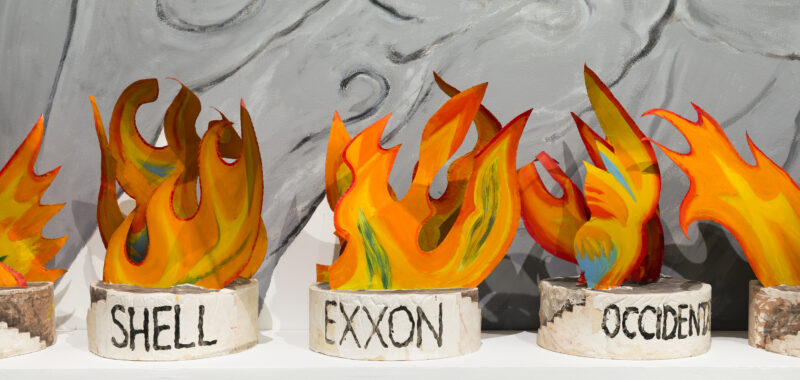

From the ravaged cityscape of the 1973 oil crisis sprang the first sweat equity co-op at 519 E 11th Street. On the roof, residents installed a two-kilowatt wind turbine paired with solar panels that supplied the community with electricity as it experienced frequent outages. Energies includes archival documents and works by Becky Howland and Gordon Matta-Clark, who were involved in local regeneration projects in the 1970s: Howland’s sculpture “Oil Tankers on Fire” (1983/1996/2024) and Matta-Clark’s Energy Trees (1972–73) drawing series. It also brings a contemporary lens to questions of energy justice through a sharply curated artist cohort.

The show radiates into the neighborhood with a nearby mural by Otobong Nkanga (whose current monumental installation at MoMA is a must-visit) and a recreation of Matta-Clark’s rosebush enclosure at St. Mark’s Church. Inside the Swiss Institute, its three floors are replete with works that collectively attain planetary scope through quirky means: Vibeke Mascini’s installation powered by cocaine confiscated in the port of Rotterdam; Saba Khan’s retro-futuristic sculpture referencing World Bank-funded hydropower projects on the Indus River; Joar Nango’s structure made of wood, reindeer sinew, and the aforementioned halibut stomachs, used in Sámi architecture for their transparent and insulating properties; and Cannupa Hanska Luger’s mirror shields devised for water protectors of the Standing Rock Reservation.

Several works document neocolonial practices of extractivism and neglect: Gabriela Torres-Ferrer streams footage of ongoing devastation in Puerto Rico after Hurricane Maria; Ximena Garrido-Lecca reveals the environmental toll on the highest-altitude, most polluted mining city in the world, Cerro de Pasco in Peru; and Liu Chuang lights an atavistic chain of makeshift torches in the declining manufacturing center of Dongguang in China. Four ballpoint “Afrolamp” drawings by Jean Katambayi Mukendi that play with the iconic shape of the incandescent light bulb punch above their weight, offering a witty commentary on the exploitation of African mineral treasures in copper-rich, energy-poor Lubumbashi.

The artworks are modest in size yet ambitious in concept, begging the question: How impactful are cerebral, historically informed interventions, in a perilous time for environmental safeguards? The exhibition’s origin story suggests an answer — the residents who erected the wind turbine were sued by the near-monopolistic Con Edison company for forcing it to buy back their surplus energy. With the unlikely support of a former Attorney General, William Ramsey Clark, they prevailed, opening a path for decentralized power production in the United States and, like the show that they inspired, planting hope in the rippling wake of small local acts.

Energies continues at the Swiss Institute (38 St. Marks Place, East Village, Manhattan) through January 5, 2025. The exhibition was curated by Stefanie Hessler, director of the Swiss Institute, with Alison Coplan, chief curator, KJ Abudu, assistant curator, and Clara Prat-Gay, curatorial assistant.