As artists, we fully — sometimes too fully — embody our creative work. This is only part of the dilemma facing Dawn Levit, the main character in Jennifer Savran Kelly’s debut novel, Endpapers (2024). “Because I’m not ready to go home. Home to Lukas,” the book opens. “Because lately I get more pleasure from spreading open the covers of a book than my own legs.”

Dawn, a book artist, is lingering after work at her job in the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s book conservation lab. A Bachelor of Fine Arts grad in her mid-20s, she was lured to this position by the chance to use the facilities to produce her own artistic work. But like many young New York artists before her, her artwork isn’t giving her much love lately. “For a long time, art had been my savior,” Dawn narrates. “Lately, it’s my spectacular failure. I’m supposed to be showing my work by now, like my former classmates, only there is no work. I’ve been vacant — of ideas, of images, and of words.” Dawn is struggling not only to find her vocabulary, but also her artistic community in the forbidding, divided world of post-9/11 New York City.

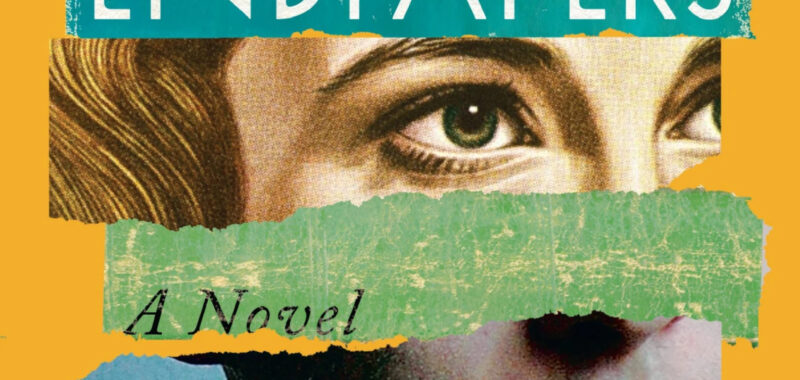

One of the great joys of Endpapers is how Savran Kelly folds Dawn’s search for artistic and gender identity into the elements of the book form. Working in the conservation lab one day, Dawn discovers a hidden 1950s pulp lesbian novel cover under the endpaper. It’s a campy illustration of a woman looking into a mirror and seeing a man’s face reflected. On the back of the cover is a handwritten letter in German from a woman named Gertrude to a woman named Marta. Though Dawn doesn’t know it yet, she has inadvertently stumbled upon a trove of content for her next piece. Unraveling the mystery of how the book cover became hidden inside another book and the surprising origins of the letter takes Dawn on a quest of self-discovery, compassion, and ultimately, self-acceptance.

Though Dawn’s art career “already feels like one of those fragile pages I watch Stacey encase in Mylar — ready to crumble to dust if I don’t do something to save it,” she gets a lucky break when she is offered a spot in a group show. At first, she thinks about saying no, terrified of the prospect of having to come up with something new in less than two months. Eventually, afraid that she is trying to “avoid everything that artmaking keeps asking me to confront,” she commits to the show.

The early 2000s was an age of artist collectives. In Endpapers, Dawn invokes that spirit by gathering a community of street artists around her to collaborate on her book project. The more that she commits to being in connection and communion with others, the stronger her artistic voice becomes: “But waiting between the covers is a living, breathing city with its own story to tell,” she writes.

Endpapers chronicles Dawn’s search for personal definition, communion, and solidarity. She savors the city for its wonders — “It’s amazing what you overhear people talking about in New York City,” she writes — and suffers in the hands of its dark rage: the streets vibrating with “equal parts love and fear, demanding both 9/11TRUTH and MUSLIMS GO HOME.” Ultimately, Savran Kelly’s rendering of the search for artistic community and finding the will to keep making art despite the realities of day jobbing and adulting is deeply nuanced and felt. It is an excellent, fast-paced read for anyone interested in the great struggle of surviving as a working artist.

Endpapers (2024), written by Jennifer Savran Kelly and published by Algonquin Books, is available for purchase online and in bookstores.