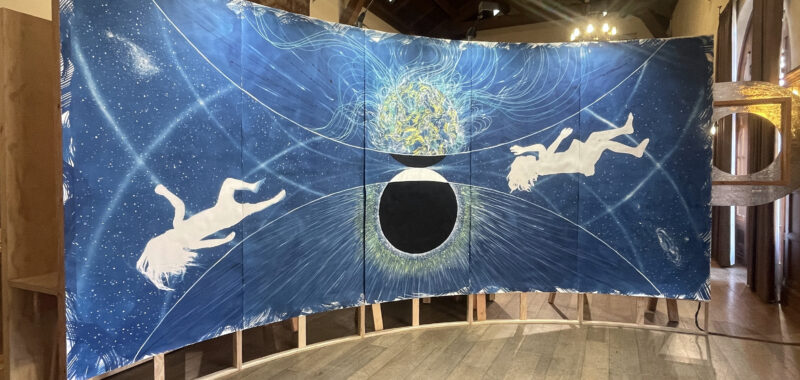

PASADENA — In Lia Halloran’s mixed media painting on cyanotype, “You, Me, and Infinity” (2024), two half-planetary bodies abut at the center of a five-panel canvas. Thin, wavy tendrils expand out from smaller particles, suggesting light, distance, frequencies, or alien signals. Two pale silhouettes of children float among the cosmos. These imprints were created by Hallohan’s children lying on the cyanotype as it was exposed in the sunshine. One of the legs is repeated in a ghostly echo, evidence of a restless toddler.

Halloran is one of the five contemporary artists who contributed new works to Crossing Over: Art and Science at Caltech, 1920–2020, the university’s contribution to PST ART: Art & Science Collide. The artists — Halloran, Lita Albuquerque, Jane Brucker, Shana Mabari, and Helen Pashgian — were inspired by a century of monumental discoveries from the physicists, engineers, chemists, and other scientists who have made Caltech one of the most elite scientific research institutions in the world. The show is divided into sections (The Infinite Lawn, Time Stream, and Powers of Ten) to cluster technological advancements into their own themed galleries, particularly in astronomy, physics, and chemistry — but that’s by no means every discipline covered in this show.

Crossing Over dips into Caltech’s extensive archive of photographs, research, class projects, books, and ephemera to demonstrate how the school has made an impact not just in California, but in the entire universe. Unknown makers used steel, wood, styrofoam, and paint to build a “Model of crystal structure of chromium carbon” (c. 1950) on campus, geological engineer Bailey Willis accidentally created a “Seismogram of earthquake in Chile made by a fruit dish scraping across a sideboard (November 11, 1922)” and “‘Var Plate’ of Andromeda Galaxy seen with the Hooker telescope (replica)” (1923) shows how Edward Hubble proved we are not alone through his work at the Mt. Wilson Observatory.

One aspect of the show that makes it a gem are the candid photographs of legendary scientists, most credited to unknown photographers. We get to see “Richard Feynman juggling at the beach” (c. 1940), a “Jack Parsons and Marjorie Cameron wedding portrait” (1948), and “Walt Disney with Roger Hayward’s moon model” (1955), as evidence that these renowned scientists were once goofy colleagues.

This thought is amplified by what may be the exhibition’s most precious objects, books by Nicolaus Copernicus, Galileo Galilei, and Johannes Kepler, all featured in the Time Stream section. The Gates Annex library, built in 1917, serves as the gallery; thick, musty journals of organic chemistry surround the artifacts. Gazing upon the etchings based on Galileo’s drawings of the moon in “Sidereus nuncius” (1610) elicited cognitive dissonance for me; these astronomers have achieved such mythic status that it’s almost impossible to imagine them as people publishing their research like any modern Caltech scientist.

Jane Brucker riffs on this sensation in her site-specific work, “Magnetic Attraction” (2024), which nestles dioramas among the stacks of books. In her carefully curated showcase of gold fragments, compasses, and eyeglasses, she uses antiques as stand-ins for knowledge that has been passed down from one academic to another. She has purposely chosen items that feel archaic, but are probably modern — like what appear to be 18th-century spectacles with the phrase “moon view” printed onto the lenses in a contemporary, sans serif typeface — to blur the lineage. The artwork was inspired by the life of her longtime friend Robert Hellwarth (1930–2021), who brushed shoulders with Nobel laureates when he was a research fellow at the university, then spent 50 years transferring research to his students at the University of Southern California.

Crossing Over can feel like Caltech patting itself on the back for its achievements, but that doesn’t take away from the awe of glimpsing its archives. Artists and scientists can both geek out over the exhibition, which shows that a biologist’s sketches of fruit flies are just as artful as Helen Pashgian’s green-hued resin orbs (which she made while an artist-in-residence at the school in 1969). It is said that everything in the universe is connected. That may be true in the universe of Caltech.

Crossing Over: Art and Science at Caltech, 1920–2020 continues at Caltech (1200 Eeast California Boulevard, Pasadena, California) through December 15. The exhibition was curated by Claudia Bohn-Spector and the project was directed by Peter Collopy.