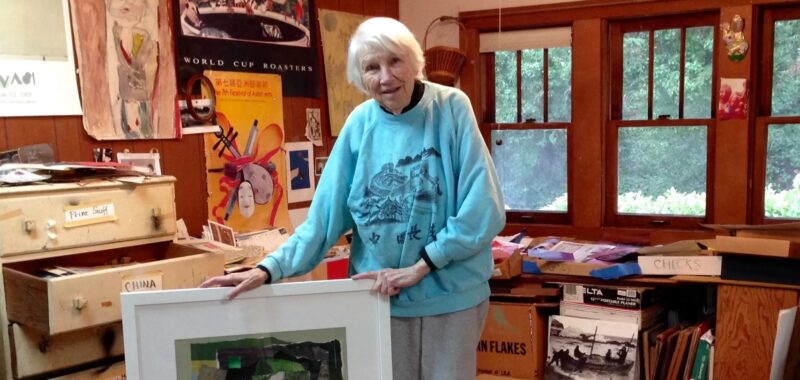

Oregon-based artist Eunice Lulu Parsons, whose practice spanned printmaking, painting, tilemaking, and collage over the course of seven decades, died in Portland on Saturday, November 16. She was 108 years old. Her granddaughter Jos Dodson Tervo described Parsons as “a legend in the Portland art community” in a Facebook post announcing her death.

“She was a force of nature and I somehow thought she would live forever, but 108 is an amazing run,” John Olbrantz, director of the Hallie Ford Museum of Art at Willamette University, told Hyperallergic. He described Parsons as “an artist who lived her life on her terms” who “took the medium [of collage] to new heights of technical virtuosity and sophistication.”

Born on August 4, 1916, in Loma, Colorado, Parsons was mainly raised in Chicago, where she took her first art classes at the School of the Art Institute when she was 11 years old. There, she studied the school’s collection of 19th- and 20th-century Modernist holdings and was particularly drawn to its Impressionist and Cubist works. In 1936, she married Allen Herbert Jensen, with whom she had three children. They moved to Portland, Oregon, and divorced in 1960.

“She knew she was in love with art, but like most women, I think the expectation was that she would get married and have children,” Bonnie Laing-Malcolmson, a former curator of Northwest Art at the Portland Art Museum who met Parsons during the ’70s, told Hyperallergic, adding that the artist “raised the kids, but was always drawing.”

At the encouragement of a neighbor, she enrolled in art classes at the Museum Art School (now known as the Pacific Northwest College of Art) in 1950. Due to financial constraints, however, she attended classes for just one year. After her divorce, she was hired as an instructor at the school, teaching full-time and part-time for just over 20 years as one of the few women faculty members. She also held teaching positions at the Young Women’s Christian Association, St. Mary’s Academy, and Portland State University.

In the early ’60s, she turned toward collage, the discipline for which she is best known, often incorporating found materials like posters, old magazine covers, ticket stubs, packaging materials, and her own silkscreen prints. She spent most of her life on a modest income (Laing-Malcolmson said she supplemented her earnings with brush drawings of birds), grew her own vegetables, and spent several hours five to seven days a week making art in the attic studio of her three-story bungalow home, which was filled “floor to ceiling” with work from other artists that she acquired by trading her own art.

She mostly exhibited at Portland galleries and Pacific Northwest institutions like the Portland Museum of Art, where her work is held in its permanent collection. Her collages, lithographs, and paintings are also housed at the Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art at the University of Oregon, the Hallie Ford Museum of Art, and Portland Community College.

“It’s hard for regional artists because often they are not recognized unless they make it in a bigger urban setting,” Laing-Malcolmson said, though she noted that the artist was “never bitter” for her lack of recognition. She added that Parsons “influenced so many artists that studied with her and later befriended her” during her lifetime.

“She was a tiny, fierce, dedicated-to-art person,” Laing-Malcolmson said.