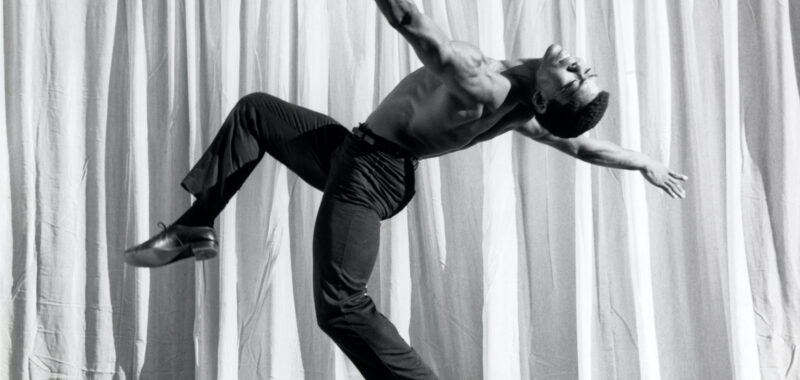

Alvin Ailey’s performing arts transcend the traditional boundaries of dance. The seminal dancer and choreographer created a living history of movement imbued with cultural memory and personal expression. Through his choreography and his company’s performances, he seamlessly interwove narratives of Black, American, and queer identity, exploring themes of struggle and liberation in performances that were both physically dynamic and deeply rooted in the human condition. His expansive vision of what modern dance could be — flexible, inclusive, and multidisciplinary — makes his work an ideal centerpiece for the Whitney’s first-ever exhibition dedicated to a performing artist.

Edges of Ailey at the Whitney Museum of American Art blends performance footage, recorded interviews, and notes from the late choreographer’s personal archive with paintings, sculptures, music, and installations by more than 80 artists. As Ailey himself reflected in a 1984 interview, “There was movement, there was color, there was painting, there was sculpture, and there was the putting it all together.” This holistic approach allows the two sides of the exhibition — Ailey’s life and work alongside art that relates to or is inspired by him — to coexist harmoniously, each enriching the other to compose a more complete story of American culture.

Among the exhibition’s direct references to dance are Barkley Hendricks’s painting “Dancer” (1977), depicting a Black woman in a white leotard set against a white ground; Senga Nengudi’s sculpture “R.S.V.P.” (1975), evoking a body or body parts through stretched nylon pantyhose and sand; and two paintings of dancers in rehearsal by Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, one of which was created specifically for this exhibition. These works are complemented by an 18-screen video projection of various Ailey performances, played on a loop throughout the space and accompanied by scores from Josh Begley and Kya Lou. Another section hosts videos of musicians, dancers, and choreographers who influenced Ailey, including Katherine Dunham, Maya Deren, Carmen de Lavallade, and Duke Ellington.

But the real lure of the exhibition lies in the opportunity to connect with the storied Alvin Ailey on a personal level through his notebooks, journal entries, letters, and other ephemera meticulously organized alongside corresponding artworks. Ailey was a scrupulous note taker, chronicling his life in painstaking detail. On Monday, September 20, 1982, he works through his daily minutiae: “Woke up at 10:30, call from Atlanta, watched soaps and drank tea, called Ernie at 12:13, Sylvia called at 2:00 to talk about ….” But in other entries, such as one from 1980 that states “nervous breakdown, 7 wks in hosp,” Ailey’s brevity highlights the overwhelming weight of the experience of a mental breakdown, a reality that might be too heavy or painful to unpack in words. Aptly placed next to this entry is Rashid Johnson’s “Anxious Men” (2016), a drawn alter-ego of the artist’s own anxieties.

Born in 1931 into a lineage of sharecroppers in rural Texas at the height of the Great Depression, Ailey was raised by his mother after his father abandoned them. Constantly searching for work, she moved them from town to town; at one point, when Ailey was just five, he helped her pick cotton. This upbringing, steeped in the struggles of Southern Black life and the spiritual grounding of the church, profoundly shaped his most iconic work, Revelations. Drawing from the gospel, blues, and spirituality that surrounded him as a child, he transformed these memories into a montage of pain, hope, and redemption. Works like John Bigger’s portrait of a weary yet resilient Black man, “Sharecropper” (1945), characterized by its dark and somber tones, or “Haze” (2023), Kevin Beasley’s landscape painting of a few trees against a yellow sky in the South, depict histories that visually resonate with Ailey’s creations.

In 1941, Ailey and his mother joined the Great Migration, leaving the South for Los Angeles, where he got his start in dancing. And yet, for all the history that shaped him, his journey — and legacy —represent only the beginning, as he continues to inspire new generations of dancers, choreographers, and artists.

Edges of Ailey continues at the Whitney Museum of American Art (99 Gansevoort Street, Meatpacking District, Manhattan) through February 9. The exhibition was organized by the Whitney Museum of American Art in collaboration with the Alvin Ailey Dance Foundation and curated by Adrienne Edwards, Engell Speyer Family Senior Curator and Associate Director of Curatorial Programs, with Curatorial Research Associate Joshua Lubin-Levy and Curatorial Assistants CJ Salapare and Katie Fong.

The exhibition is accompanied by a series of dance performances. Check the Whitney website for dates and times.