In the weeks leading up to the inauguration of the Ram Mandir (temple of Ram) in Ayodhya on January 22, saffron flags dotted streets, marketplaces, and private balconies across the north Indian city. They were attached to bikes, cars, and auto-rickshaws, and forcibly hoisted onto a church by a group of men chanting Hindu nationalist slogans. Featuring an image of the Hindu god Ram standing with a bow and arrow in front of the outline of the temple, the bright-orange flags, a color associated with the Hindutva movement, are a sign of celebration — the deity’s so-called return to his birthplace. The temple was built on contested land where the 16th-century Babri mosque once stood, before being demolished by a Hindu nationalist mob in 1992. The Ram Mandir’s inauguration marked a victory for Hindu nationalists and for the Ram Janmabhoomi movement, spearheaded by right-wing politicians in the late ’80s, to reclaim Ram’s birthplace.

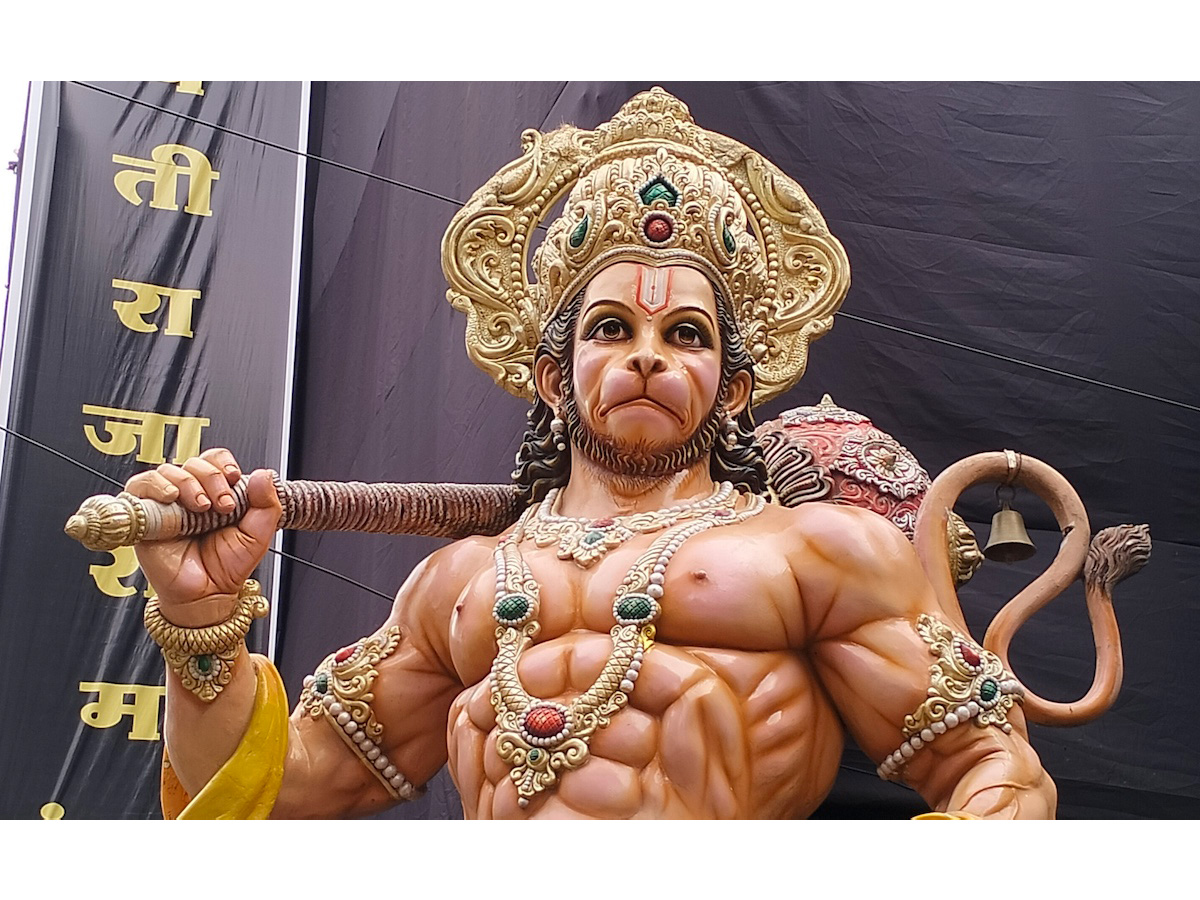

“When the Ram Janmabhoomi movement picked up, there was this idea that Hindus are victims of historical invaders, and so they needed to have more aggressive, more muscular figures to represent Hinduism,” Indian designer and graphic artist Orijit Sen told Hyperallergic. Lord Ram, the hero of the Hindu epic Ramayana, was transformed from a serenely smiling god into a warrior wielding a bow and arrow and sporting a six-pack. Other Hindu gods have also changed in appearance, from the battle-ready Hanuman to the impossibly muscular Shiva. The qualities associated with them have morphed as well, from softer virtues of devotion and humility to a fiery morality. While the idol inside the Ram Mandir in Ayodhya is of an innocent five-year-old Ram who has returned home, the images on the flags, posters, and banners across the country portray him as a fearsome warrior.

Gone are the curved, graceful figures — the Hindu iconography of the 21st century, often in digitally rendered images, conveys a hypermasculine, aggressive new Hinduism to galvanize people into action. And it has become a chilling extension, and tool, of the Hindu right in India.

From the 6th-century rock-cutting in the Ellora caves to the miniature paintings from the 19th century, Hindu gods were portrayed as graceful, rounded, serene figures in art and sculpture. Historian and writer Anirudh Kanisetti explained that during the medieval period, artists often cast them as idealized royals to give kings more authority as lieutenants or partners of the gods. They had lithe bodies, heavily bejeweled and wearing the latest fashions. These renderings also reflected distinct cultural understandings of sex, masculinity, and gender, as in the Bhakti poetry praising the beauty and sensuality of the gods. “They are depicted as strong and powerful,” Kanisetti told Hyperallergic, “but always in a way that’s effortless. As though their power emerges from their divinity, rather than from going to the gym.”

Raja Ravi Varma, one of India’s first modern artists, incorporated Western realism into his paintings of the gods in the 1890s. Using human models to illustrate deities, his works were mass-produced, and public spaces were soon filled with calendar art of humanistic gods from the Ramayana and Mahabharata epics. Religious iconography continued to evolve over the next century within pop culture and Hindu gods were depicted in media from Amar Chithra Katha comics and to the popular 1987 Ramayan TV show.

This evolution can be clearly traced through depictions of Hanuman, a monkey deity. Traditionally portrayed in Pahari paintings from the 17th to 19th centuries as a full-fledged monkey, Hanuman’s only human elements were a crown and a dhoti (long loincloth). He is devoted to Ram and portrayed as docile and playful, usually shown sitting at the feet of Ram and Sita, his wife.

But the version of Hanuman that is now ubiquitous across India is starkly different. The image dubbed “Angry Hanuman” shows a dramatically shadowed, frowning face in saffron and black. Created by 25-year-old graphic designer Karan Acharya in 2015, this scowling sketch of Hanuman went viral within a year. It can be found on the windshields of cars and trucks, flags, t-shirts, watches, and even WhatsApp display photos.

“The ‘Angry Hanuman’ seems to signify a muscular, aggressive Hindutva,” said Kanisetti. “One of the founding myths of Hindutva is that all Hindus were ‘humiliated’ by Muslim invaders, and that this was because Hinduism wasn’t sufficiently aggressive.”

Even before the meteoric rise of the Hindu nationalist movement in 2014 following the election of Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi, the move toward a more contemporary version of Hinduism was already underway. The success of the International Society for Krishna Consciousness (ISKON), also known as the Hare Krishna movement, the Art of Living organization, and figures such as Sadhguru shows that younger generations were open to more modern portrayals of their religion. Images of a muscular Shiva smoking weed became an icon of a new, chill version of Hinduism, showing up on posters in cafes, on t-shirts, and as a common tattoo choice. “There’s this image of Indian nationhood that’s being created,” Kanisetti said. “One that is simultaneously traditional, based on an imagined idea of a single Hindu tradition, and one that is contemporary, based on a recent aesthetic of coolness, and it taps into 21st-century anxieties about masculinity and inferiority compared to the West.”

Extremist groups and political parties, including the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), have harnessed the potential of social media to shape religious messaging. It’s a successful strategy given the rise of affordable internet and phones in the country, an unemployment crisis, and a fragile democracy in which religious tension is only growing. The imagery that has occupied public spaces in the past few years shows Hindu gods who match the anger and machismo of nationalist groups, frequently led by men. Kanisetti added that they also tap into the insecurities, anger, and fears that some Hindu Indians harbor. On social media, AI-driven retellings of mythological stories offer visuals of a glorious, imagined past, with gods towering over their subjects, muscles rippling and weapons in hand. Commenting on these AI-based visualizations, Kanisetti noted that while they might be unconvincing to many, younger generations might believe in this depiction of India’s “glorious” past.

“There is a kind of imaginary being created to which these figures belong, and it’s not really an Indian one,” Sen added. “It’s drawing from Hollywood and superhero comics, from Western popular culture. And the reason we’re seeing it, absolutely without a doubt, is because the Hindu right is creating and pushing it.”

Arvind Rajagopal, Media Studies professor at New York University and author of Politics After Television: Hindu Nationalism and the Reshaping of the Public in India (2009), illuminated the transition from an earlier sense of unchanging values into rapidly changing imagery.

“There is now a constant revision of how gods are portrayed, throwing aside traditional texts, but always claiming continuity with tradition,” Rajagopal told Hyperallergic. “And this is something very different. It’s meant to terrorize.”