A simple change of perspective can crack open a universe of possibilities — and in Rachel Martin’s galaxy, the artwork greets you upside down.

Her body arched in a backbend, a female figure donning a Tlingít mask perches on red-nailed fingers in an extraordinary balancing act, playfully beckoning visitors into the artist’s first solo show in New York City.

True to its name, Bending the Rules gathers 15 works on paper that defy convention in more ways than one. I felt a magnetic pull toward the Queens-based Tlingít artist’s imaginative field of vision, drawing from Indigenous Northwest Coast formline practices to conjure her own artistic vocabulary. Martin grew up between California and Montana’s Fort Peck Indian Reservation and connected with Tlingít culture later in life, most recently through learning to speak the language. Here, her capacity to weave cultural traditions together and imbue them with her distinctive voice has translated into inventive drawings that center the joy of communing, confiding, and sharing meals.

“If our table could talk” (2024), the anchoring centerpiece of the show, is a natural gathering place for other visitors set with eight delectably drawn plates arranged for a shared meal of Indigenous dishes. Nourishment is the artist’s conceptual guiding star, rendered in her elegant lines as a plate of salmon and peas shared with someone you love. I’ve often felt alienated by sparse shows at this and other glitzy Manhattan galleries, but Martin’s exhibition breathes fresh air into the space.

A spirit of play and precision characterizes several smaller and mid-sized works across the show, all full of delicious detail that compels viewers to come close and revel in the little things. In “Hot Girl Summer” (2024), minute formline u-shapes, crescents, and ovoids compose a figure in repose — perhaps enjoying her last hoorah before demure fall. Martin’s graphite and colored pencil linework is equal parts humorous, tender, and liberated. Paper tooth generously shows through. Graphic sensibility abounds. It’s any drawing devotee’s wildest dream.

Another figure in a backbend sports an eyebrow in the shape of a bird in “Wolf Brows 4 Life” (2024); as a fellow thick-eyebrows girly, I felt seen. And who wouldn’t smile at “Yéil’s Sock Money” (2023), in which a character in a raven mask mischievously squirrels a $20 bill into the safety of their crew sock?

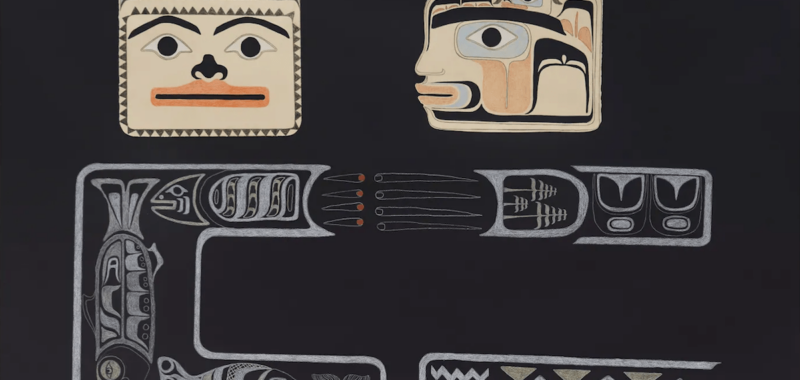

These witty pieces orbit stunning monumental works, with “Love is a tide is a taste is a seed is a tree,” a singing composition stretching over five feet tall, running as a steady beat to complement Martin’s wry point of view. Its two masked subjects kneel and reach out to one another, despite the distinct channels running through their geometric bodies: one of fish, the other of abstract patterns and shapes.

Martin’s effortless blend of humor and tenderness is perhaps best exemplified by a striking drawing of a masked figure wearing a pair of Converse and a sweeping shawl adorned with formline motifs, titled “She’s a 10 but she boils herring eggs until they’re all white and rubbery” (2024). But the artist serves a more filling meal in this exhibition; and, needless to say, she ate.

Rachel Martin: Bending The Rules continues at Hannah Traore Gallery (150 Orchard Street, Lower East Side, Manhattan) through November 9. The exhibition was organized by the gallery.