Last week, in a quiet corner of Columbia University’s Manhattan campus, a vibrant structure drew attention with its bold colors and profound messages. This sukkah, a traditional symbol of Jewish harvest celebrations, was erected by Jewish students on October 16 as a statement on themes of liberation, displacement, and solidarity. Its intricate artwork and powerful words invited passersby to engage with the deeper meanings stitched into its fabric.

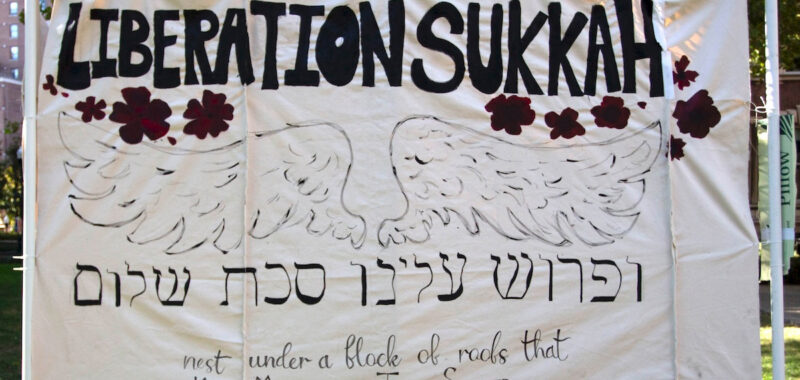

The first panel announced itself in black letters: “LIBERATION SUKKAH.” Below, delicate wings extended outward over the Hebrew phrase “Ufros Aleinu Sukkat Shalom,” meaning “spread over us a shelter of peace.”

“It’s a line from a prayer we recite daily during the Hashkiveinu,” explained a Columbia student involved in building the sukkah. (Two students interviewed for this piece asked not to be identified for fear of retaliation by university leadership.) “We chose this line because ‘sukkat’ means shelter, the same word for ‘sukkah.’ It’s a sukkah of peace.”

Just beneath the Hebrew text, a quote from the poem “V’ahavta” (2016) by Aurora Levins Morales stood out: “… nest under a block of roofs that keep multiplying their shelter.” Surrounding the quote were vibrant poppy flowers, symbols of remembrance and resistance.

The Liberation Sukkah emerged at a time when the Columbia University campus had already witnessed student encampments against the ongoing violence in Gaza and the Occupied West Bank as well as the university’s investment ties to companies linked to the Israeli military.

The Liberation Sukkah was not the work of a single artist. It was a joint effort, brought to life by students in just a few hours. “I couldn’t give a number,” one student said. “It was a very collaborative process.”

“By creating common messages in the sukkahs, those building them refuse to be ‘artists’ in the Western tradition of named individuals attested to by a signature, as if a work was a check,” said Nicholas Mirzoeff, professor and chair of the department of Media, Culture and Communication at New York University and a Hyperallergic contributor. “What is being created is the common, or perhaps better, the commune.”

Circling around the sukkah, a panel captures attention with another excerpt from Levins Morales’s poem: “Defend the world in which we win as if it were your child.” The phrase hovered above detailed illustrations of the Shivat Haminim, seven sacred plants in Judaism — wheat, barley, grapes, figs, pomegranates, olives, and dates.

“We wanted to acknowledge these plants, which are native to Palestinian land but hold significance in Jewish tradition as well,” explained the student.

The center of this panel featured Handala, a famous Palestinian cartoon of a displaced child, created by Naji al-Ali in 1969. Barefoot and in rags, Handala has become a symbol of Palestinian resistance.

Another section of the sukkah included a reimagined line from the Yiddish socialist Labor Bund movement song “In Ale Gasn.” Originally a 1930s rallying cry against the oppressive rule of the Tsar in present-day Ukraine, students transformed its call to “bring down the Tsar’s walls” into a plea to “bring down apartheid.”

The final side of the sukkah presented a quote from poet June Jordan — “I said I loved you and I wanted genocide to stop” — framed by olive trees hand-painted by the students.

Mirzoeff noted that the sukkahs are “a form of performance art for peace.”

While the artwork tells its own story, the sukkah itself carries historical and spiritual weight. Traditionally, a sukkah is a temporary structure built for Sukkot, the Jewish festival that commemorates the Israelites’ 40 years of wandering in the desert after escaping slavery in Egypt. These makeshift shelters remind the Jewish community of their ancestors’ reliance on God for sustenance and protection.

“For us, it’s impossible to talk about these shelters without acknowledging what’s happening to Palestinians today,” one student noted. “Jewish shelters in the desert provided safety, but tents in Gaza do not protect from bombs.”

“What matters here is the refusal of religion as the justification for violence and war,” Mirzoeff said.

The sukkah’s bamboo roof adhered to the Jewish law of using something that was once alive but no longer connected to the earth.

While Jewish tradition calls for spending time in the sukkah, even sleeping in it during Sukkot, the students acknowledged their limitations. “Unfortunately, it’s too cold,” one student said with a smile.