An impressive array of architects, from Ludwig Mies van der Rohe to Heatherwick Studio, Le Corbusier to Álvaro Siza, have designed structures at world fairs, or expos. Here we round up the 12 most significant.

The Crystal Palace, London 1851, by Joseph Paxton

Created to host the Great exhibition in 1851, which the Bureau International des Expositions regards as the first World Expo, the giant Crystal Palace building was designed by engineer Joseph Paxton.

At 563 metres long and 39 metres high, the modular iron and glass building was the world’s largest glazed building when it completed. Paxton’s design was based on a module size of 1.2 metres tall and 25 centimetres wide, which was the size of the largest mass-produced panes of sheet glass available.

After the six-month exhibition in London’s Hyde Park, the structure was dismantled and rebuilt in south London in an area that now takes its name. Unfortunately, the building was completely destroyed in a fire in 1936.

Crystal Palace had a significant impact on future architecture, with Pritzker Architecture Prize winner Norman Foster describing it as the “birth of modern architecture.

Eiffel Tower, Paris 1889, by Gustave Eiffel

Undoubtedly the most famous structure created for an expo, or world’s fair, the Eiffel Tower is one of the world’s best-known structures.

Rising to 330 metres, the hugely ambitious structure was almost twice as tall as any other man-made structure when it completed. It wasn’t until the Chrysler Building opened, over 40 years later, that it lost its title as the world’s tallest building.

Designed as a temporary structure that would both be the centrepiece of the Exposition Universelle of 1889 and mark the centenary of the French Revolution, the tower was only meant to remain in place for 20 years. However, due to its use as a radio mast, it remained after this period and became the symbol of Paris.

Grand Palais, Paris 1900, by Henri Deglane, Albert Louvet, Albert Thomas and Charles Girault

The Grand Palais is the most impressive of a host of landmarks built in central Paris for World’s Fairs.

Alongside the Petit Palais, Pont Alexandre III, Gare d’Orsay railroad station and the Paris Métro Line 1, the Grand Palais was built ahead of the Exposition Universelle of 1900.

Set on the Champs-Élysées, the heart of the Grand Palais is a vast and intricate barrel-vaulted atrium, which was made from more than 6,000 tonnes of steel as one of the last great naturally lit exhibition spaces.

The building was restored by French studio Chatillon Architectes in 2024 ahead of the Olympics, when it hosted fencing and taekwondo events. Earlier this year, Dezeen named the Grand Palais as the most significant building of 2024 in our list of the 25 most significant buildings of the 21st century.

German Pavilion, Barcelona 1929, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe and Lilly Reich

Designed by Van der Rohe and Lilly Reich, the German Pavilion at the 1929 International Exposition in Barcelona is undoubtedly one of modernism’s most significant buildings.

The pavilion was commissioned to give “voice to the spirit of a new era”, according to its commissioner Georg von Schnitzler. With a flat roof supported on thin columns, the building exemplifies many of the ideals of future modernist works.

Van der Rohe and Reich also designed the Barcelona Chair for the pavilion, which itself has become a modernist classic.

The original structure was dismantled in 1930, with the existing reconstruction completed in 1986.

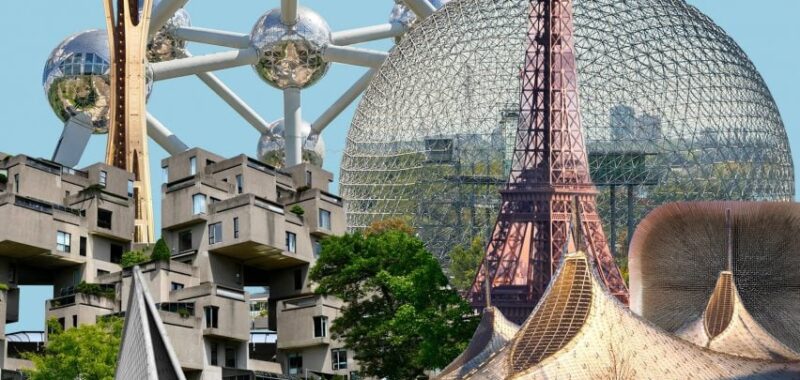

Atomium, Brussels 1958, by André Waterkeyn, André Polak and Jean Polak

The centrepiece of the 1958 Brussels World’s Fair, the 103-metre-high Atomium is a giant representation of an iron crystal magnified 165 billion times.

It was named Atomium as a combination of atom and aluminium, which the nine 18-meter-diameter spheres that represent iron atoms were initially clad in.

Visitors to the structure could visit exhibitions contained within six of the nine spheres, which were connected by escalators in the tubes connecting the globes.

Much like the Eiffel Tower, the Atomium was planned as a temporary structure, but eventually became permanent and is now the most popular attraction in Brussels, with visitors still able to climb the structure.

Philips Pavilion, Brussels 1958, by Le Corbusier and Iannis Xenakis

Also at the 1958 Brussels World’s Fair, Le Corbusier and Iannis Xenakis created a tent-like structure as a pavilion for the electronics company Philips.

The pavilion hosted a multimedia audiovisual show named Electronic Poem, which aimed to highlight innovations in post-war electronics. The reinforced-concrete structure was formed of nine hyperbolic paraboloids.

“I won’t make you a pavilion with facades,” said Le Corbusier. “I’ll make you an electronic poem and the bottle that will contain it.”

The building was demolished in 1959.

Space Needle, Seattle 1962, by John Graham & Company

The 184-metre-high Space Needle was built as the centrepiece for the 1962 World’s Fair, which had the theme The Age of Space, with the aim of becoming a permanent, distinctive landmark for the city.

Once the tallest structure in western USA, the futuristic form consists of a sleek hourglass-shaped tower topped with a UFO-like disc that contained a pair of restaurants.

In 2018, American studio Olson Kundig Architects carried out an extensive overhaul of the structure, adding “the world’s first and only revolving glass floor”.

Habitat 67, Montreal 1967, by Moshe Safdie

Held to mark Canada’s centennial year, Expo 67 had a wealth of boundary-pushing architecture, including the Habitat 67 housing.

Located on the Saint Lawrence River overlooking the main expo site, the housing block was designed by Israeli-Canadian architect Moshe Safdie. It was created to demonstrate the potential of pre-fabricated construction for urban housing aligned with one of the expo’s themes – habitat.

The landmark demonstration project consists of 354 irregularly stacked, concrete boxes that contained 158 apartments. The block’s arrangement allows for each apartment to have plentiful light along with a private terrace.

US Pavilion, Montreal 1967, by Richard Buckminster Fuller with Shoji Sadao

Towering over the expo site, the US Pavilion became the iconic symbol of Expo 67. The pavilion was contained within a geodesic dome that had become the calling card of American architect Richard Buckminster Fuller.

With a 76 metre diameter, the globe-shaped structure, created entirely of a triangular web of three-inch steel tubes, was the largest of Buckminster Fuller’s geodesic domes. It comfortably enclosed the seven-storey building containing the pavilion’s exhibits.

Originally covered in a thin acrylic membrane, this outer skin burned off in a fire in 1976, leaving the structure exposed and in many ways enhancing the structure’s impact.

In 1995, the building reopened as the Montreal Biosphere – a museum promoting the environment and its protection. In 2021, The New York Times selected the building as one of the “25 Most Significant Works of Postwar Architecture”.

German Pavilion, Montreal 1967, by Frei Otto and Rolf Gutbrod

Another architectural highlight of Expo 67 was Frei Otto’s tent-like German Pavilion, a breakthrough structure for the architect and engineer, who would go on to win the Pritzker Architecture Prize and RIBA Royal Gold Medal.

Supported on eight slender steel masts, the complex-looking form was made from a steel cable mesh topped with a translucent textile membrane.

The tensile canopy structure would influence the roof of the 1972 Munich Olympic stadium, which was also designed by Otto and which Dezeen recently named as one of 15 Olympic architecture icons.

Portuguese National Pavilion, Lisbon 1998, Álvaro Siza Viera

Built to form the main entrance to Expo’98 in Lisbon, the Portuguese National Pavilion was designed by Portugal’s best-known architect, Álvaro Siza Viera.

The building was divided into two distinct elements: a solid element for receiving heads of states and an open public plaza. Siza shaded this plaza with an incredibly thin, 70-metre-long concrete canopy.

“The result in my opinion is interesting, because it’s a very special half and a very almost banal second building side-by-side,” he told Dezeen in a film about the pavilion.

Seed Cathedral, Shanghai 2010, Heatherwick Studio

The dramatic Seed Cathedral was designed by Heatherwick Studio as the UK Pavilion for the 2010 World Expo in Shanghai.

The structure had a timber core pieced by 60,000 fibre-optic rods – each 7.5 metres long – that gave it a distinctive, hairy appearance. In a collaboration with the Kew Royal Botanic Gardens’ Millennium Seed Bank Project, the rods contained a total of 250,000 plant seeds at their tips. After the event, the rods were distributed to UK and Chinese schools.

The pavilion won the Bureau International des Expositions’ gold award for best pavilion design in its size category at the event and later won the RIBA Lubetkin Prize.

The photography is courtesy of Shutterstock, unless stated.

The post The 12 most architecturally significant Expo buildings of all time appeared first on Dezeen.