VIENNA — Hannah Höch’s art was disruptive, irreverent, and, for its time, extremely loud. It presaged, by at least 80 years, present-day discourse over the ubiquity of mass-media imagery in the digital age. Assembled Worlds at the Belvedere Museum is the first major museum retrospective in Austria dedicated to the iconic German artist. She was a leading figure of the Berlin Dada movement and is credited as one of the inventors of collage and photomontage. A prestigious German award for women artists is named after Höch, whose commentaries on the mass-media typecasting of women — featuring fashionable-looking figures with monstrous heads or smiles, or no heads — delivered a subversive critical blow to bourgeois views on gender and class as single women entered the work force and became a consumerist demographic for the first time.

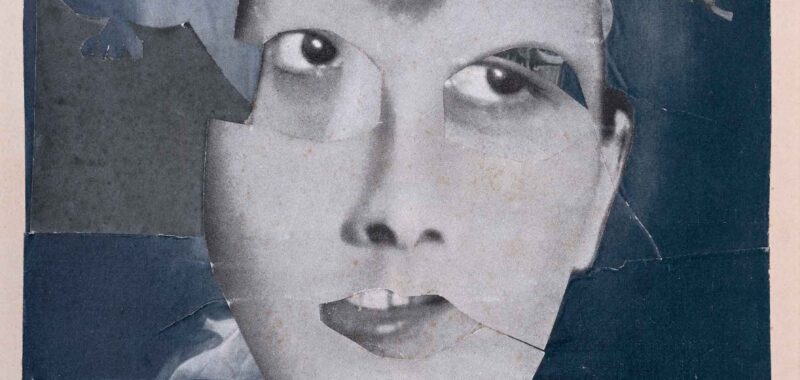

With the rise of National Socialism, Höch’s social commentary took a dark and disturbing turn; her works penetrated the ideological abyss of fascism and exposed its murderous propaganda. To reduce her work to the political would be a mistake, however: True to her Dada origins, it was her sharp wit and love of nonsense that prevailed. Assembled Worlds focuses on Höch’s photomontages and her understanding of them as “static films,” presenting them alongside experimental films by artists such as Hans Richter, László Moholy-Nagy, and Fernand Léger. The juxtaposition is revealing; it highlights her use of rhythm as an abbreviation of time and demonstrates the ways in which the montage technique and its abrupt cuts — as in the photomontage “English Dancer” (1928), with its mask-like face constructed from superimposed layers of morphing identities — were better suited to conveying the disjointed political, social, and ethical realities of the modern age.

Höch’s works were brash and stylish, and wielded their power through images taken from the latest glossy journals. Her sharp-witted analyses of modern visual culture tapped into the popular iconography and crises of the interwar years, contextualized in the films shown in the exhibition: the lingering trauma from WWI; the confluence of hyperinflation and reckless hedonism during the Weimar period; the explosion of technological advances; the emergence of a new, never-before-seen media-driven commercialism; and redefined gender roles and the social anxiety they inspired. “The Father” (1920) deconstructs patriarchal authority as women athletes dance around a man in drag cradling a baby to whom a boxer delivers a blow. And the menacing bird in “Flight” (1931), made two years before Hitler came to power, foreshadows the peril, persecution, and dehumanization to come. In 1933, Höch’s works were denounced as “cultural Bolshevism” and she was banned from exhibiting. She buried her archive in her garden in the Berlin suburb of Heiligensee to save it (and herself) from the fate that befell many of her avant-garde artist friends, who were deemed “entartet” (“degenerate”), and persecuted or killed, their artworks ridiculed and destroyed.

After World War II, Höch increasingly dedicated herself to Surrealism. Her works became more fantastical, more connected to nature and its timeless rhythms, more visionary: in the photomontage “Vivace” (1955), hints of an eye, lip, and collar seem to suggest an identity in flux, a dreamlike countenance in constant motion. Yet the World War II-era images are the most captivating, such as “Hungarian Rhapsody,” a collage from 1940, the year Hungary joined the Axis powers. An androgynous figure somewhere between a circus acrobat and a soldier is suspended in a precarious balance on a gigantic wheel; several looming centrifugal patterns are about to slip between the wheel’s spokes and yank the figure into a funnel below. Above, in the sky, is a softly undulating contour, like a line of foam left by waves on a beach — or perhaps it’s a thunderhead, ominously cutting across the darkening sky.

Hannah Höch: Assembled Worlds continues at the Belvedere Museum (Rennweg 6, Vienna, Austria) through October 6. The exhibition was curated by Martin Waldmeier of Zentrum Paul Klee, with Assistant Curators Johanna Hofer and Ana Petrovic.