Greenland is in the headlines as President-elect Trump threatens to buy or simply take the territory — perhaps along with Canada and Panama.

Some media outlets have suggested this is no mere empty threat. For countries neighboring the U.S., this may sound like a renewed Manifest Destiny. For many, this is just ridiculous posturing by a leader craving the spotlight.

This surreal moment does, however, provide an opportunity to better understand Greenland’s unique status, if only to put to rest Trump’s misplaced ambitions.

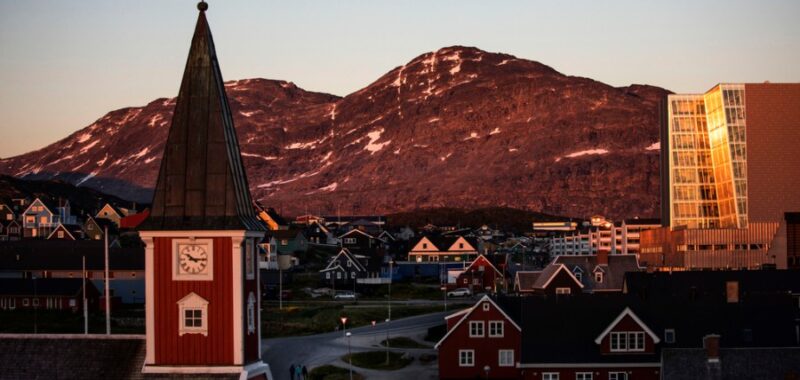

Often described as the world’s largest island, Greenland is immediately to the east of the Canadian territory of Nunavut, with whom it shares cultural and historical links. Colonized by the Kingdom of Denmark in the 18th century, it retains an Indigenous majority. Inuit peoples constitute about 90 percent of the territory’s 56,000 residents, with the others mostly being Danes concentrated in the capital city of Nuuk.

Although part of Denmark, Greenland is also partially independent from it. In 1979, Greenland was granted autonomous status. In 2008, 75 percent of Greenlanders voted to expand self-government powers. Today, Greenland (Kalaallit Nunaat) has its own parliament, flag, language policy, control over education, resource management and even membership in international organizations.

In a highly fragmented political party system, Greenland’s parliament (Inatsisartut) has long been ruled by Siumut, a left-wing social democratic party. In 2021, the left-leaning separatist party Inuit Ataqatigiit won a plurality of seats, allowing its leader, Múte Bourup Egede, to become prime minister. This means that Greenland is currently led by a separatist, although in coalition with other parties. The ruling party focuses a great deal on Greenlandic sovereignty, including rejecting rare earth mining projects that favor foreign companies and endanger the local environment.

The barriers to Greenland becoming independent are considerable. Its fragmented legislature has no single dominant party, which undermines any sense of the island having a single voice. The territory has important regional divisions, as one might expect in a sparsely populated region, especially as the countryside resists centralization from Nuuk. Greenland has rich natural resources, namely fisheries and mining, but it remains dependent on economic transfers from Denmark.

Perhaps the primary factor limiting the likelihood of independence is that the territory enjoys real autonomy, with the potential for more. While hardly impossible, the world has yet to see a special region gain considerable autonomy, and use this as a stepping-stone to independence. This is because meaningful self-government is often considered superior to independence or incorporation.

It also makes the host country seem less threatening, since minorities are recognized by national leaders and are ruled by their own group. Separatists who are forced to govern must also make compromises and sometimes see their policies fall short. All told, regions such as Greenland with real self-government are not likely to gain independence.

This brings us back to Trump’s threat to annex Greenland. To “purchase” the island makes no sense, as it is not Denmark’s to sell. Nor would Inuit peoples sell their homeland. It is true that Greenland wants the U.S. to be an ally and a trading partner, but joining the U.S. would run counter to its quest for self-rule. As Greenland’s leaders have made clear, there is no logic in trading one Western colonial power for another.

Greenland is open for business, but it is not for sale. Inuit peoples in Greenland also understand the limited nature of self-rule for Puerto Rico and Native Americans. The U.S. has a poor track record in sharing power with minority nations, and it would be no different for Greenland under President Trump. And as for the threat of invasion, this would involve one NATO member attacking another, theoretically triggering a war between the U.S. and its allies.

An American Greenland is little more than bluster. Greenland is enjoying a growing sense of self-government in association with Denmark. It seeks to diversify its foreign relations and trading partners, seeking better terms with mining companies, as well as with Canada, including deepening ties with Inuit in Nunavut.

Threats of annexation run contrary to the potential partnerships that would best serve the interests of the people in Greenland and the U.S.

Shane Barter is a professor of comparative politics at Soka University of America in Aliso Viejo, Calif.